Albany Congress, conference in U.S. colonial history (June 19–July 11, 1754) at Albany, New York, that advocated a union of the British penal colonies in North America for their security and defense against the French, foreshadowing their later unification. Seven colonies—Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island—sent delegates to the conference, which was convened by the British Board of Trade to work out plans for joint defense measures and to help cement the loyalty of the Iroquois Confederacy, which was wavering between the French and the British in the early phases of the French and Indian War.

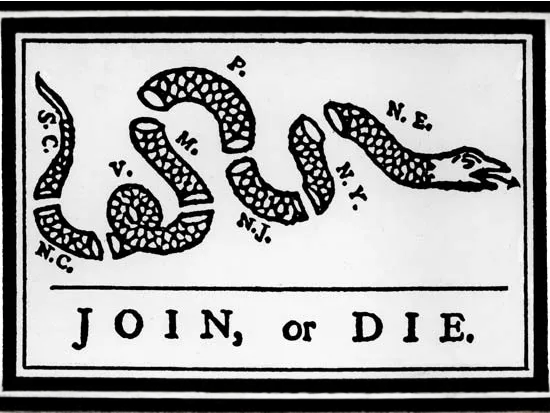

After receiving presents, provisions, and promises of redress of grievances, 150 representatives of the five Nations of the Confederacy withdrew without committing themselves to the British cause. In addition, delegates to the Congress advocated practical measures resulting in closer regulation of Indian affairs and westward migration of pioneers. Moreover, Benjamin Franklin, serving as a Pennsylvania delegate, presented the so-called Albany Plan of Union, which provided for a loose confederation presided over by a president general and having a limited authority to levy taxes to be paid to a central treasury. Although the plan was approved by the delegates, neither the Crown (jealous of its authority) nor any of the colonial assemblies (unwilling to sacrifice sovereignty) approved it, and the war was conducted under the old system. “The different and contrary reasons of dislike to my plan made me suspect that it was really the true medium,” Franklin later wrote, “and I am still of opinion it would have been happy for both sides the water if it had been adopted.” Indeed, despite the fact that the issue here was not independence, the Albany Plan proved to be a farsighted document that contained the seeds of the solution to colonial problems later adopted in the Articles of Confederation and in the Constitution.

Long before Europeans came to North America, a thriving democratic system was established in the heart of what would become New York State. The Confederacy, known to the French colonists as the Iroquois League and the English colonists as the League of Five Nations, was already well-established, united in a confederation of nations governed by their Great Law of Peace.

Are the original inhabitants of the land that is now New York State, as well as parts of contemporary Canada. They established a system of governance known as the Great Law of Peace, which dates to the 12th or 13th century. This system embodied principles that resonated with the very core of democracy. The Great Law of Peace is said to have been brought to the nations by the Great Peacemaker, who helped the previously conflicting nations to come together in a confederacy on the shores of Onondaga Lake near today’s Syracuse.

At the heart of the rotinonsonni system was the “Great Council,” a council composed of representatives from each member nation. While it might not have been a direct antecedent of today’s Congress, it shared the fundamental principle of representative democracy. These representatives, or sachems, deliberated and made decisions by striving for consensus, a concept that is a cornerstone of American democracy. Consensus decision-making, the process where all parties involved must agree on major decisions, was central to the rotinonsonni governance. They understood that fostering unity and ensuring that every voice was heard was essential. This emphasis on consensus echoes in the American political system where the framers of the U.S. Constitution aimed to reach agreements and compromise among diverse interests.